By Enver Robelli

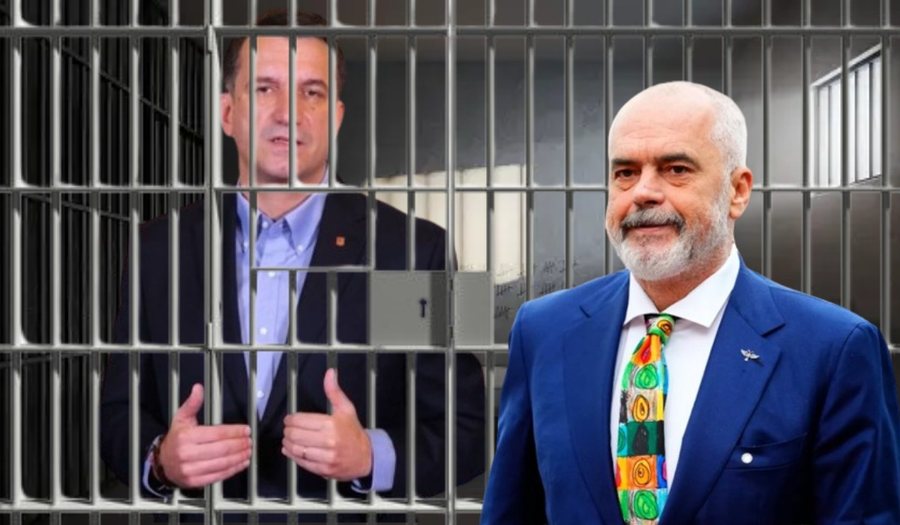

In a lengthy interview published in the magazine of the German weekly newspaper DIE ZEIT, Albanian Prime Minister Edi Rama does not mention Tirana Mayor Erion Veliaj by name, but interprets his arrest and the arrests of other officials as a success of the new justice system in Albania. Rama says that for the first time since the declaration of independence in 1912, an independent prosecutor is investigating high-ranking officials. According to him, politics is no longer a shield for the corrupt. Rama presents this as a major achievement of his government and proof that Albania has - finally - built a judicial system that no longer protects corrupt politicians. Rama does not personally defend Veliaj, nor does he clearly distance himself, but uses the occasion to strengthen the narrative of justice reform, which, according to him, functions on new grounds and is independent of the government.

DIE ZEIT's interview with Edi Rama, the Prime Minister of Albania since 2013, begins with a description of an earlier clash between journalist Stefan Willeke and Rama after a critical article published in May 2024. Rama had called the journalist in question in outrage and then invited him for a conversation. This is a testament to Rama's talent for playing the role of a chameleon. This is a method that Rama has tried several times with Western journalists. After critical articles, he contacts them, reprimands them, indirectly threatens them with legal consequences, then, when he notices that this did not impress the journalists, he changes the record, invites the journalists to Albania and shows himself ready to give an interview. This is how the process developed until the interview with DIE ZEIT.

In the interview, Rama initially speaks humorously about his physical height (1.98 m) and his past as a professional basketball player, linking this to the authority that is sometimes attributed to the body. He believes that charisma plays a more important role than height. Rama recalls the horror of his childhood during communism in Albania, when, being taller than others, he immediately caught the eye of teachers and other authorities. He recounts the brutal attack on him by secret service structures in 1997, when he was still an intellectual critical of Sali Berisha's regime, and how this experience transformed him, both physically and especially spiritually.

Rama describes his life in isolated Albania under the dictatorship of Enver Hoxha as a reality with two parallel worlds: what could only be said inside the house, and what had to be said outside. In this environment of ideological repression, he began as a talented provocateur in art and debate.

Rama recalls his return to Albania from Paris after the death of his father, the sculptor Kristaq Rama, and his unexpected acceptance of the post of Minister of Culture in 1998, the very day of his father’s funeral. He describes his mother’s reaction, who severely reprimanded him for this step, reminding him of the consequences that political engagement could have in Albania. For Rama, this was the moment when “the humor of the universe” decided that an artist should become a minister.

During the interview, he states that he never thought of entering politics. He describes himself as an artist who sought freedom in a regime that imposed rigid frameworks even in art. But then, he sees politics as an “art in its own right” that requires patience and talent.

In relation to international personalities, Rama expresses great appreciation for Angela Merkel, whom he describes as the only one who did not let herself be influenced by charisma. He believes that if she were still Chancellor in 2022, the war in Ukraine could have been avoided. Towards Donald Trump, although he had been critical at first, Rama today expresses sympathy, calling him “a great chance for Europe”, especially on the issue of peace with Russia. He criticizes the West for not taking the word “ceasefire” seriously, but does not explain what the conditions of this ceasefire would be.

Rama mentions his collaboration with Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni on setting up reception centers for asylum seekers in Albania. During a summit, he theatrically knelt before her, a gesture that also reflects his passion for self-deprecation.

He also talks about the much-discussed project with Jared Kushner, Donald Trump's son-in-law, to build a luxury resort on a peninsula and island in Albania. Rama says the project is progressing.

Albania's prime minister is reacting to accusations of links to organized crime, calling them "monstrosities" produced by the opposition and hostile media. He says he has been accused of everything from homosexuality to rape and domestic violence. He denies everything and says the "strongest opposition" he has is his wife at home, who holds him accountable for everything every evening.

On the issue of press freedom, Rama has an ambivalent relationship with the media. He states that he values independent journalism, but criticizes the way it is presented in the local press. On certain occasions he has excluded journalists from press conferences, while the case of journalist Ambrozia Meta, whose face he touched during an interview, has been widely cited as an example of his authoritarian behavior. The journalist accuses Rama of building an “economic dictatorship” and of contempt for the poor. Journalist Meta says that Edi Rama “distributes building permits to trusted people of criminals. He does not act like a socialist, even though he is the chairman of their party. He does nothing for the poor and the elderly. Mostly he is trying to secure his place in the history books - as the father of the nation.”

On the other hand, Rama highlights the justice reform as a major achievement of his government. He says that for the first time since Albania's independence, the justice system is treating senior officials independently. He emphasizes that his party is no longer a "shield" for the corrupt.

However, critics are numerous and harsh. Enton Abilekaj, a well-known journalist, accuses Rama of having started collaborating with organized crime since the legalization of cannabis cultivation. According to him, criminals provide him with political support. Journalist Andi Bushati from the independent platform Lapsi says that Rama's balance sheet is negative and that his diplomatic success is a facade to legitimize his autocracy. Fatos Lubonja, a former political prisoner and former friend of Rama, calls him a "narcissist" and compares him to Vladimir Putin, adding that Rama controls everything and does not accept criticism. According to him, the biggest problem is the Albanians themselves who allow such a man to govern.

Rama responds that Lubonja is disappointed because he himself went from civil society to power and was declared a “traitor to the cause.” For him, politics is a mechanism that requires management, not just passion. Rama refuses to talk about his major mistakes as prime minister, saying he will do so only after leaving office.

For Rama, power is a “wild beast” that deforms you if you’re not careful. He says he tries to maintain contact with reality by pretending he doesn’t fly business class, his wife drives her own car, and he doesn’t have state-paid servants at home. Meanwhile, in the evenings, he says, the “toughest opposition” he knows is the one waiting for him at home – his wife, an economist and tireless critic, who, he says, keeps him grounded.

Not only in this part of the interview, other journalists, for example local and independent, would also have some questions for Edi Rama - questions that would be quite unpleasant. Thus, the interview in DIE ZEIT is an attempt by him to appear as a nonchalant politician, skillful in decisions and talented in maintaining his image as a politician who is not involved in any affair, while dozens of his associates are under investigation or in prison.

Exclusively for A2 CNN, reprinting in other media without authorization from A2 CNN is strictly prohibited. (A2 Televizion)