By Enver Robelli

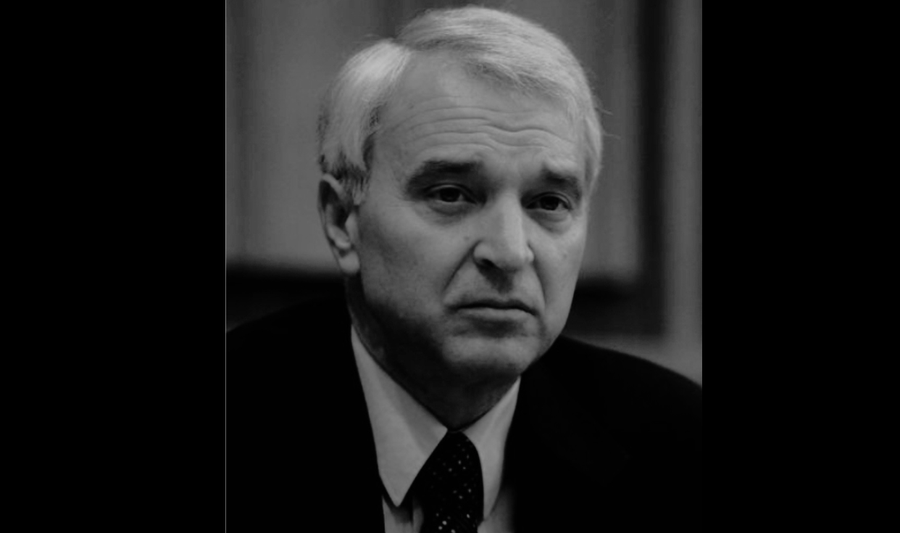

On the occasion of the death of Dr. Bujar Bukoshi, Prime Minister of Kosovo.

1.

Nonchalance does not mean carelessness. It means more of a benevolent redemption. Dr. Bujar Bukoshi was, in his own original way, a champion of nonchalance. “Come on, I brought grapes from the vineyard in Suhareka,” he told me on a summer day in 2017. He held his back with his hand, said he felt a slight pain, but there was no sign of concern on his face. Even when he received a serious diagnosis, he maintained his nonchalant, often dark humor. He said: “Where did this disease find me when, for example, 1.2 billion Chinese people live in this world.” With unparalleled willpower, with the help of his family and many friends, he faced the disease as much as he mocked it. Today, in the early hours of the morning, Bujar Bukoshi, the first Prime Minister of the Republic of Kosovo, closed his eyes.

2.

I am writing this text for Bujar as a friend and interlocutor, not primarily as a politician. Throughout the dramatic phases that Kosovo has gone through when he got involved in politics, great turns, great expectations, great desires, great dreams have been as frequent as disappointments and failures, often through no fault of his own. But in the end, what matters is the result: on June 10, 1999, Bujar Bukoshi was getting ready to return to a liberated Kosovo after almost a decade in exile. The day before, Serbian forces had signed the capitulation in Kumanovo, on June 10, 1999, NATO attacks had ceased. In fact, this is the date of Kosovo's liberation. There may be something symbolic and divine in the fact that his death coincides with the 26th anniversary of Kosovo's liberation.

3.

His punctuality was German. “I’ll be at the Collection restaurant in 7 minutes.” He would arrive in an old jeep, a relic left over from the Battle of Koshara. No shame, no posing, no disgusting scenes of Balkan politicians. He would order a coffee, exchange a few words with the waiter, open a pack of cigarettes and embark on a journey through the new history of Kosovo. This wandering began at the Suhareka post office, in Prizren in the 1960s, in the dark time of Aleksandar Ranković’s repression, in Belgrade in 1968 engulfed by student protests, in divided Berlin in the 1980s, where Bujari earned his doctorate in urology and returned to serve in Kosovo’s largest hospital in Pristina. Just as he had served in the 1970s in Drenas. Dr. Bujar Bukoshi was among those Kosovo Albanians who were not inferior to others in the then socialist Yugoslavia. He could talk about medicine and literature as an equal to anyone from Ljubljana to Skopje. As a representative of an Albanian society that was trying to catch the emancipation train. A society that immediately after World War II was still in the dark, with about 50 percent of illiterate men and over 70 percent of illiterate women. While he was a student in Belgrade, his brother fled to Albania. Although Yugoslavia was a repressive, autocratic state, with elements of dictatorship, Bujar was not hit by any collective punishment, as was practiced in Albania, for example. He continued his studies, graduated, later went to Germany, learned German and specialized in an important medical field. In Pristina in the 1980s, he caught the eye of the regime as politically unsuitable. For this, he was punished, for example by not being given an apartment, while technical workers were also favored due to their loyalty to the regime.

4.

“I called myself a prime minister in exile, but in essence I was, like many other colleagues, just a knocker on the big, hard-to-penetrate doors of Western diplomacy,” he told me on a beautiful sunny day as we swam to an island in Ksamil, when Ksamil was still a village with two deckchairs and half a restaurant. He was the prime minister of a more virtual state, but not one to be ignored. The superiority of Kosovo’s politicians of the 1990s was as absurd as it was fortunate: compared to other Balkan figures with harsh features, Dr. Bujar Bukoshi could be mistaken for a German doctor to whom you entrust your health problems, while Dr. Ibrahim Rugova for a literary critic who doesn’t push his chair in the bar, but lifts it into the air and puts it back in its place so as not to disturb the guests. "They surprised us with their human normality," a German general told me years later at a meeting on the shores of Lake Ohrid, where one of those conferences organized by Western foundations was being held.

5.

When Viktor Meier, the correspondent of the German newspaper “Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung”, retired in the mid-1990s, Bujar Bukoshi immediately hired him as an advisor. In a photo from that time, Dr. Rugova, Dr. Bukoshi and Dr. Meier are seen entering the State Department in Washington. Bujar’s contacts with German journalists have been close and over the years have become friendly. They see Bujar as the “German of Pristina”, not only because he spoke German, but also because of his rebellious spirit. After Kosovo’s independence, Bujar Bukoshi found himself in the position of Deputy Prime Minister of Kosovo. One day he called me and told me that he would come to Zurich the next day and then we would go to Viktor Meier’s house to present the decoration that the then President of Kosovo, Atifete Jahjaga, had awarded to the German journalist (who was Swiss by birth, so he lived near Zurich). Bujari arrived in Zurich, without pomp, he had not requested a car or any ceremonial drama from the Kosovo embassy in Bern or the Consulate in Zurich. We took a taxi and I remember that the driver almost refused to take our money for the service after Bujari spoke at length about the African country the driver came from and about the dictator of that country who had ruled in the 60s or 70s. “Have you been there?”, asked the taxi driver. “No, no, I just read it”, replied Bujari.

Viktor Meier and his wife welcomed us with great kindness and remembering the past that at times - at that time - seemed to never pass. It was a moment of relief for two men who each in their own way and with passion had helped Kosovo to be independent. Viktor Meier with his sharp writings on the events in Yugoslavia, Bujar Bukoshi with his contribution to a difficult period in Kosovo's history. In the fall of 2014 we went again to Viktor Meier's village near Zurich, this time to attend the farewell mass in his memory. He had passed away on November 22, 2014.

“See you at the vineyards in Suhareka,” Bujar told me before taking the train to Zurich airport. He got into the carriage like a completely ordinary person. It was not our last meeting, but it seemed to me that that day, after the mass and lunch in memory of Viktor Meier, Dr. Bujar Bukoshi was returning home with a sense of pride that he had not only witnessed an important chapter in the history of Kosovo. (A2 Televizion)