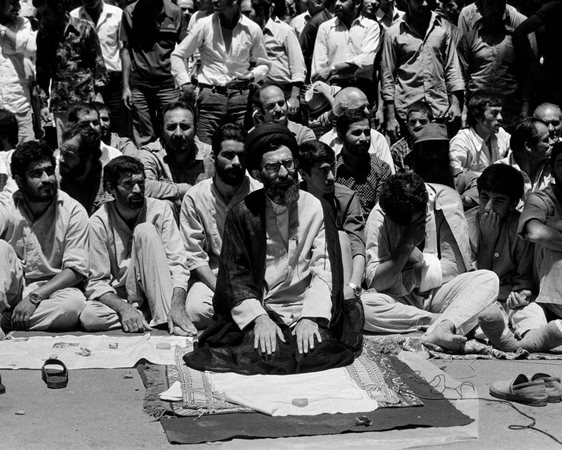

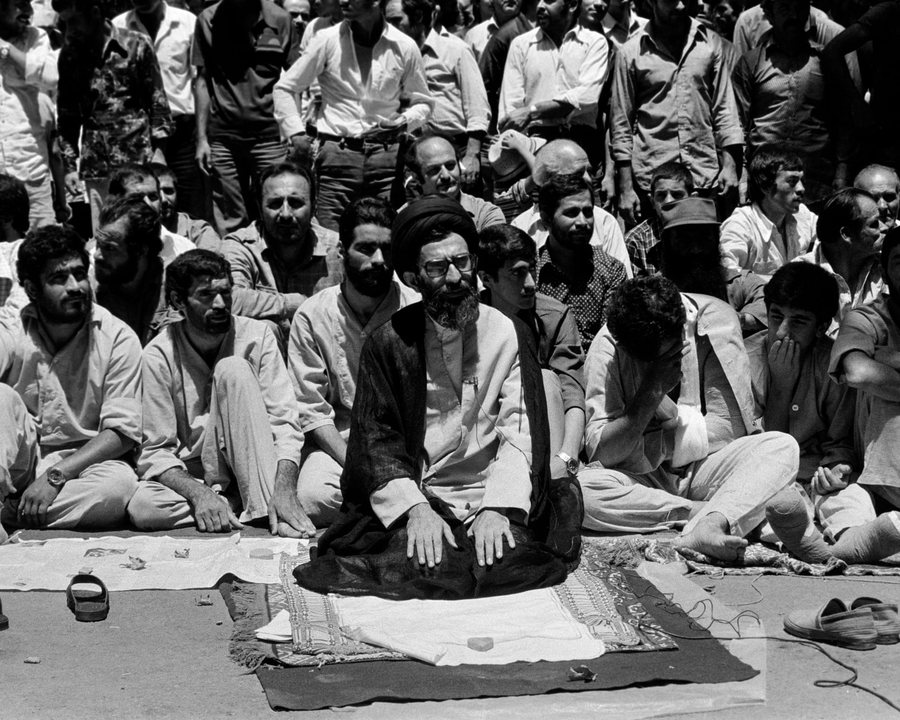

When he appeared in public for the first time in five years in October, Iran's supreme leader, Ayatollah Ali Hosseini Khamenei, delivered an uncompromising message. Israel "will not last long," he told tens of thousands of supporters in a Friday sermon at a mosque in Tehran.

“We must stand up against the enemy by strengthening our unwavering faith,” he told the audience. Khamenei was 84 years old.

Just days earlier, Israel had killed Hassan Nasrallah, the secretary-general of Hezbollah, with massive bombings at the group's headquarters in Beirut. The killing was a personal blow to Khamenei, who had a long-standing relationship with Nasrallah.

The Israeli air offensive against Iran, launched on Friday, was another shock to the regime, writes A2 CNN. It prompted harsh reactions from Tehran, including a barrage of missiles and drones towards Tel Aviv. However, even Iran's response does not seem to be able to stop the Israeli attacks. Iranian air defenses are proving powerless, and the alliance of Islamist militias that Khamenei had built as a mechanism for intimidation against Israel appears to have collapsed.

Khamenei now has few options available, a situation that this cautious, pragmatic, conservative, and ruthless revolutionary has always tried to avoid.

Origin and early activism

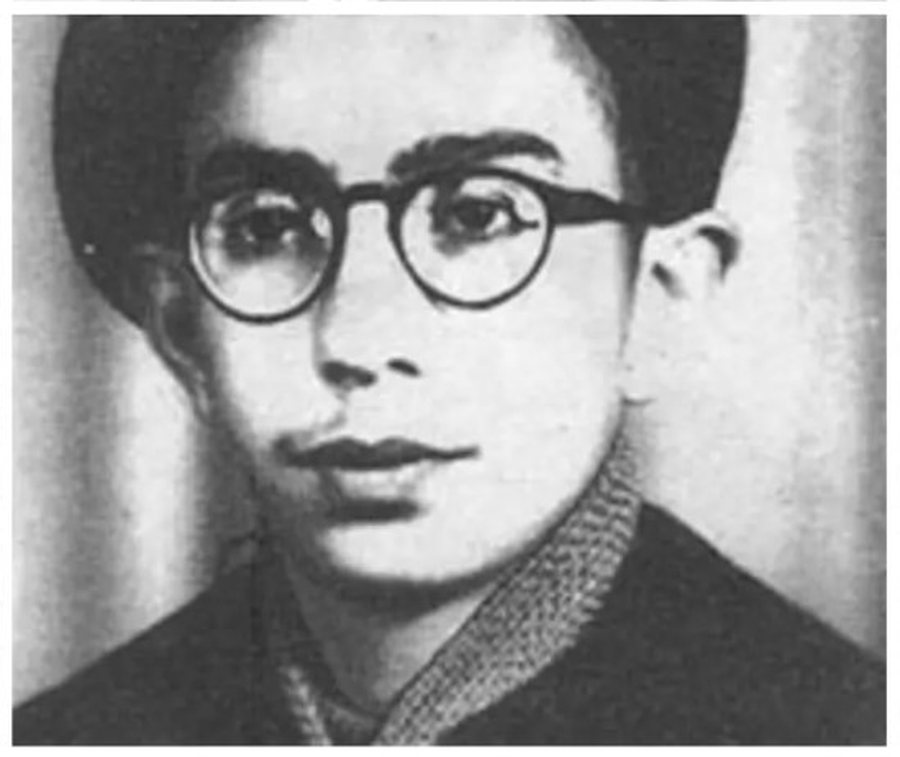

Born the son of a modest cleric in the holy city of Mashhad in eastern Iran, Khamenei took his first steps as a radical in the heated political climate of the early 1960s. At the time, Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi had launched a broad reform project that was widely opposed by the country's conservative clerics.

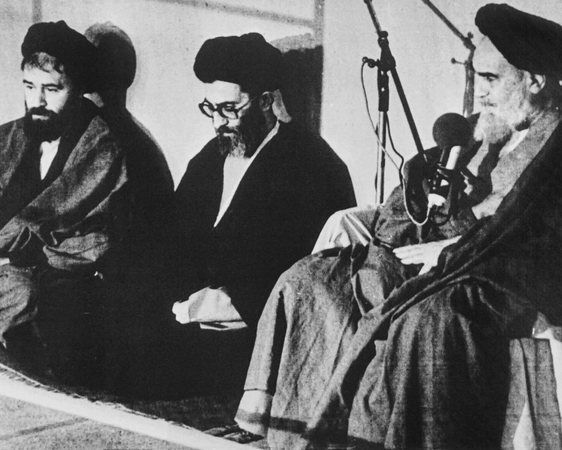

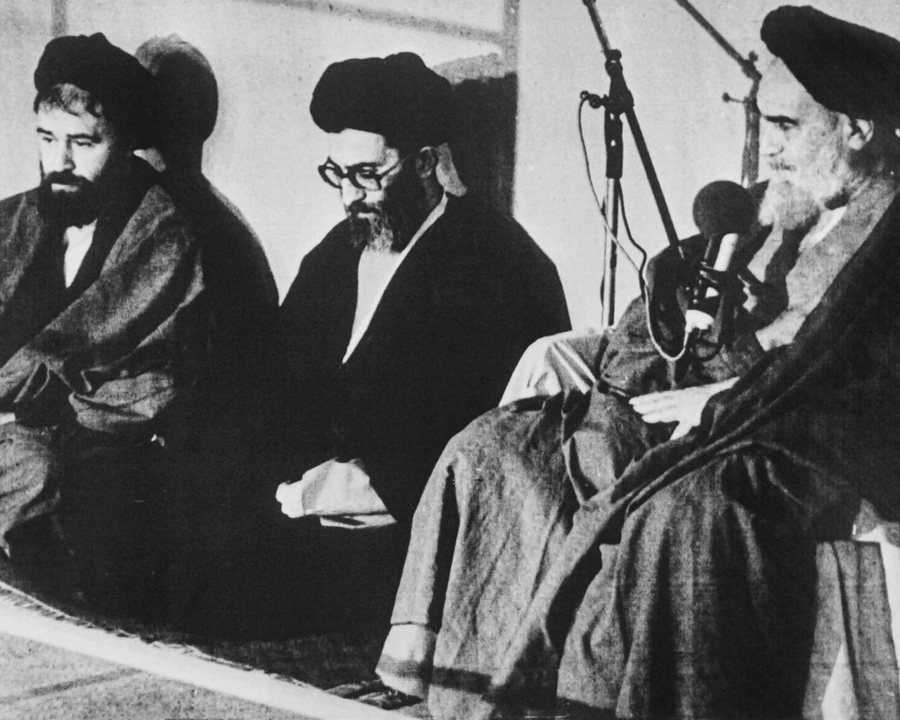

As a religious student in Qom, an important center of Shiite theology, Khamenei was influenced by religious tradition and the radical ideas of the rising opposition leader, Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. By the late 1960s, he was carrying out covert missions for the exiled Khomeini and organizing networks of Islamic activism.

Ideological influences and connections with the East and West

Although an admirer of European literature, particularly Tolstoy, Victor Hugo, and Steinbeck, Khamenei was also drawn into the anti-colonial ideologies of the time, as well as the widespread anti-Western sentiment. He translated into Persian the works of Sayyid Qutb, an Egyptian thinker who would inspire generations of Islamic extremists, and was influenced by authors who criticized the “Westernization” of Iranian society.

Arrested several times by the Shah's secret services, Khamenei nevertheless managed to participate in the mass protests of 1978, which forced him to leave and enabled Khomeini's return.

Rise to power and role as president

As Ayatollah Khomeini's favorite, Khamenei rose quickly through the ranks of the new Islamic regime after the revolution. In 1981, after an assassination attempt that left him paralyzed in one arm, he was elected president, a largely ceremonial position at the time.

Appointment as supreme leader

After Khomeini's death in 1989, Khamenei was chosen as his successor after the constitution was changed to allow a figure with fewer clerical ranks to take the top role. With far more power than his predecessor, he quickly consolidated control over the fragmented Iranian state apparatus.

One of the main pillars of his power became the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), a very powerful military, social, and economic force. But Khamenei, ever the pragmatist, also formed alliances with other powerful factions.

Reforms, repression and foreign policies

In the 1990s, he further tightened his grip, eliminating rivals and rewarding loyalists. Even poets he once admired were persecuted by the secret services. Opponents abroad were physically eliminated. Relations with Hezbollah were consolidated.

When the reformist Mohammad Khatami won the presidency in 1997, Khamenei allowed him some autonomy but did not allow the regime's ideology to be compromised. In the late 1990s and after the September 11 attacks, he did not hinder efforts to reach out to the United States and followed Khomeini's example in rejecting weapons of mass destruction.

However, he supported the IRGC's efforts to undermine US forces in Iraq after the 2003 invasion, and to expand Iranian influence in the region, using proxies as a means of pressure on Israel.

The axis of resistance and the strategic cost

Khamenei invested heavily in the so-called axis of resistance: Hamas in Gaza, Hezbollah in Lebanon, the Houthi movement in Yemen, and Shiite militias in Syria and Iraq. However, this strategy appears to be collapsing under intense Israeli attacks. The alliance with Syria ended with the fall of Bashar al-Assad's regime in December.

Lifestyle and the end of an era

Living in a modest compound with his family on Palestine Street in Tehran, Khamenei has always insisted on his modest lifestyle. However, some have questioned this image, calling it propaganda. However, his reputation for modesty has served as a shield against popular discontent.

For more than three decades in power, Khamenei has navigated internal and external pressures to preserve Khomeini's legacy and his own power.

Now, in declining health and advanced age, facing serious domestic crises and a loss of regional influence, Khamenei faces the greatest challenge of his life. The brutal balance he has so carefully built over decades may be coming to an end. (A2 Televizion)