Russia is now “producing three times more ammunition in three months than all of NATO does in a year,” NATO Secretary General Mark Rutte recently told the New York Times.

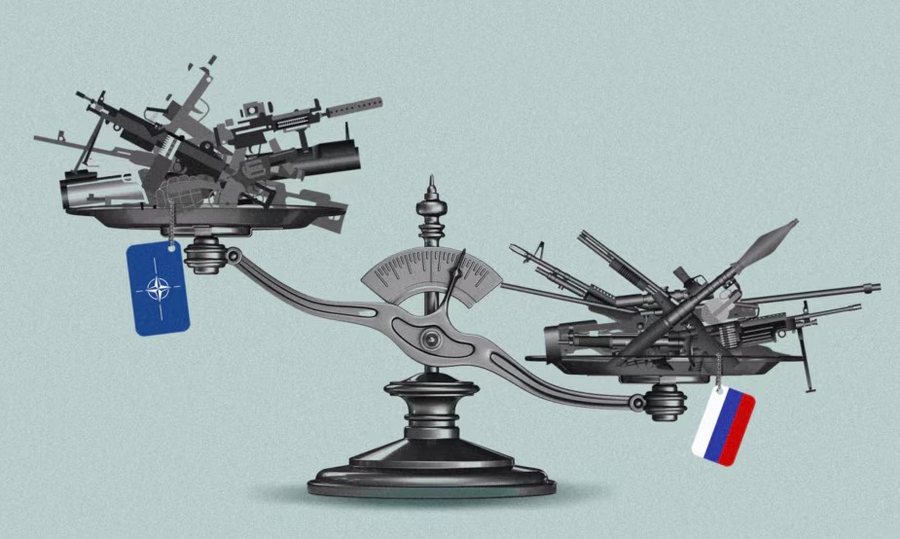

Radio Free Europe (RFE/RL) and the Conflict Intelligence Team (CIT) analyzed Russian and Western weapons production to assess whether Russia really has such a large production advantage over the United States and its allies – and in which weapons categories – artillery, ammunition, tanks, aircraft, missiles, drones and air defense – each side has an advantage.

Fact or exaggeration? Production of NATO and Russian artillery ammunition

It is not the first time Rutte has claimed that Russia is outpacing NATO in terms of artillery production. In April, during an interview with CBS, he said that Russia is “producing four times more ammunition than all of NATO produces in a year.”

Ukrainian and Western officials estimate that Russia produced about 2-2.3 million artillery rounds in 2024, an increase from about 1.25 million produced in 2022, as Moscow is investing heavily in expanding its production capacity.

Meanwhile, the US plans to increase production of 155-millimeter shells to 1.2 million per year by the end of 2025, while Europe produces almost the same number – the Rheinmetall plant in Germany alone plans to produce up to 700,000 per year – according to conservative estimates.

Current US production of shells is 40,000 per month, or just under half a million per year, meaning that in total, the US and EU have produced about 1.7 million shells this year.

To produce three times as many in three months, as Rutte said, Russia's factories would need to produce a massive 20.5 million shells this year.

According to CIT's analysis, factory expansions in Biysk, Kazan, and other locations could allow Russia to produce about 4 million 152-millimeter and 122-millimeter shells per year.

Shells need weapons

Russia continues to rely heavily on its stockpile of Soviet-era artillery systems for the shells it produces, while the number of howitzers it has produced has fallen from around 12,000 in 2022 to over 6,000 in mid-2024. According to CIT analysts, Russia produces fewer than 100 self-propelled howitzers per year of the Msta-S, Giatsint-K and Malva types.

NATO has a clear lead in this regard: France plans to produce 144 CAESAR artillery systems by 2025, while Poland will double production of AHS Krab to 100 units per year. Slovakia is expected to produce 40 Zuzana howitzers, while the US produces 216 cannon tubes for M777 weapons annually.

Heavy weapons

One aspect where Russia likely has an advantage is tanks.

Like artillery, much of its tank production comes from repairing and modernizing Soviet tanks it has in its inventory. This accounts for the majority of the roughly 1,500 tanks that, according to Christopher Cavoli, former NATO Supreme Allied Commander for Europe, Russia is expected to deliver to its military by 2025.

However, Russia has significantly increased production of its modern T-90M tank, producing around 280 per year.

Most countries in Europe, meanwhile, produce very few tanks. France has not produced a single Leclerc tank in more than a decade, while Britain has ordered 148 new Challenger 3 tanks, which are expected to be delivered by 2030. Germany is an exception, producing 50 Leopard 2A8 tanks per year.

The US buys 109 M1A2 Abrams tanks a year – the military says this figure could increase to 420 if necessary – and also modernizes up to 200 older models.

Air superiority

While Russia produces more tanks, the US and the EU outpace Moscow in terms of fighter jet production by at least four times. Russia is estimated to be able to produce 50-60 fighter jets a year, including multi-role aircraft like the Su-57 and strategic bombers like the Tu-160M2. Despite sanctions, the country is producing more aircraft than it did before it launched its invasion of Ukraine – in 2018, the Russian military received only 36 new fighter jets.

However, NATO production is much higher. The US company Lockheed Martin will deliver over 170 F-35 fighter jets this year, in addition to dozens of Rafale (France), Eurofighter Typhoon (European consortium) and Gripen (Sweden) aircraft produced by EU countries and other NATO allies.

Air defense

As Russia launches missile barrages into Ukraine, and Ukrainian drones strike deep inside Russia, the production of air defense systems has been thrust into the spotlight.

According to Military Balance, an annual assessment of military capabilities worldwide, there were 248 S-400 batteries in 2024 and an additional 18 in 2025, implying a production capacity of about 36 systems per year. The production of other systems, such as the Tor, Buk and Pantsir, is more difficult to estimate, due to a lack of data.

Raytheon produces about 12 Patriot missile defense systems per year, while German company Diehl plans to produce eight IRIS-T systems by 2025, as well as 800 to 1,000 missiles for them each year. NATO also produces the NASAMS system, developed by Norway and the US, which can use AIM-120 AMRAAM or AIM-9X missiles. The US produces 1,200 and 2,500 units of each missile per year, respectively.

However, the lack of complete data makes it difficult to determine exactly how many air defense systems and missiles each side produces. What is clear is that, with Ukraine and Russia continuing to suffer strikes from simple drones, current production rates are insufficient to effectively protect them from one of the newest and most enduring features of this war: mass-produced, low-cost strike drones.

Drone warfare

According to Ukraine, Russia produces about 5,000 long-range drones of various types every month, or 60,000 per year. This includes the Geran-2 attack drones (the Russian version of Iran's Shahed drones) and the Gerbera, an unarmed drone used as a decoy drone to overwhelm Ukrainian air defense systems.

NATO currently does not produce any drones comparable to these cheap suicide drones, while the US has chosen to use much more expensive unmanned aircraft, such as the Reaper and Global Hawk.

Russia also produces over 200 cruise and ballistic missiles per month, according to Ukraine's military intelligence agency, bringing annual production to between 2,400 and 3,000 missiles. The US, meanwhile, is estimated to produce 700 JASSM cruise missiles and 500 ATACMS ballistic missiles per year.

This gives Russia the edge in terms of suicide and hover drones.

In the event of a war between Russia and NATO, NATO air defenses would be in a better position to neutralize the threat from drones, compared to Ukraine's air defenses, which have suffered from a lack of fighter jets since the beginning of the invasion, analysts from CIT said.

While Russia has the advantage in missile production, its air defenses, which often struggle even against simple Ukrainian drones, are likely to have serious problems protecting the country's airspace from NATO missiles./ REL (A2 Televizion)